My Step By Step Process For Taking Conceptual Lecture Notes In Obsidian

You can watch the video accompanying this blog post up above but keep in mind it's slightly outdated (some of the templates are different) while the text below is not.

Before I discovered Personal Knowledge Management I took notes like most other students do, sequentially jotting down what the professor says verbatim, identically annotating the slides, or multitasking by answering texts, looking for clothes on Amazon, and watching a football game.

That last one is no joke. I once saw a guy watch the World Cup through an entire two-hour class. What a stud.

There are two major problems with this type of notetaking:

- It forces you to organize notes the way the professor gives you the information. But the professor might not have organized the content in a way that makes sense to

- It makes you a Cookie Cutter Student because all of your notes will look almost exactly the same as the other students. When I took notes in this way, school didn't excite me as it does now.

The solution I have found is conceptual notemaking.

In this article, I'm going to show you how to conceptually notemake by explaining:

- What conceptual notemaking is

- My conceptual notemaking process:

- Before class

- During class

- After class

- After the Semester

- How you can adapt the process for STEM

What is Conceptual Notemaking?

Conceptual notemaking is a form Notemaking that uses concepts as the fundamental unit of knowledge management.

Instead of notetaking predominantly through sequential format, you take notes on individual concepts and link them together. I believe that there are no rigid disciplines in the universe, only concepts. All disciplines--Biology, Neuroanatomy, Behavioral Statistics, American History, etc.--are just highly related concepts linked together into a coherent and more easily digestible form.

If everything we can learn is a mix of interrelated concepts than it makes no sense to create notes that treat classes as isolated.

And yet that is exactly how most students take their notes!

Conceptual notemaking allows my Behavioral Neuroscience notes on Dopamine to get linked to a note from my independent reading on Social homeostasis.

My notes on the differences between emotional focality across cultures from my Social Psychology class get linked to a note on Attachment Theory.

My notes on information consumption in the age of the internet get linked to my notes on the Lindy Effect.

Pretty cool right?!

Not lets talk about how you can do this yourself.

My Conceptual Notemaking Process

Not all those who wander are lost. - J.R.R. Tolkien

Hearing about conceptual notemaking after notetaking as a cookie cutter student will probably feel overwhelming.

But the process of conceptual notemaking is remarkably simple. It's the execution that's hard. Let's go through my process:

- Before class

- During class

- After class

- After the Semester

Keep in mind the whole time that there is no objective "right" way to write conceptual lecture notes.

This is simply the way that I have found most effective.

Before class

Before you even take your first notes on a lecture for class, you want to get an understanding of the progression of information you will be getting throughout the semester.

This way, you have already primed your brain to be ready to connect class concepts together.

I explain how to do this in my article The Four-Step MOC Creation Process I Use to Maximize Understanding of my College Classes in Obsidian so I won't be showing the process here.

During class

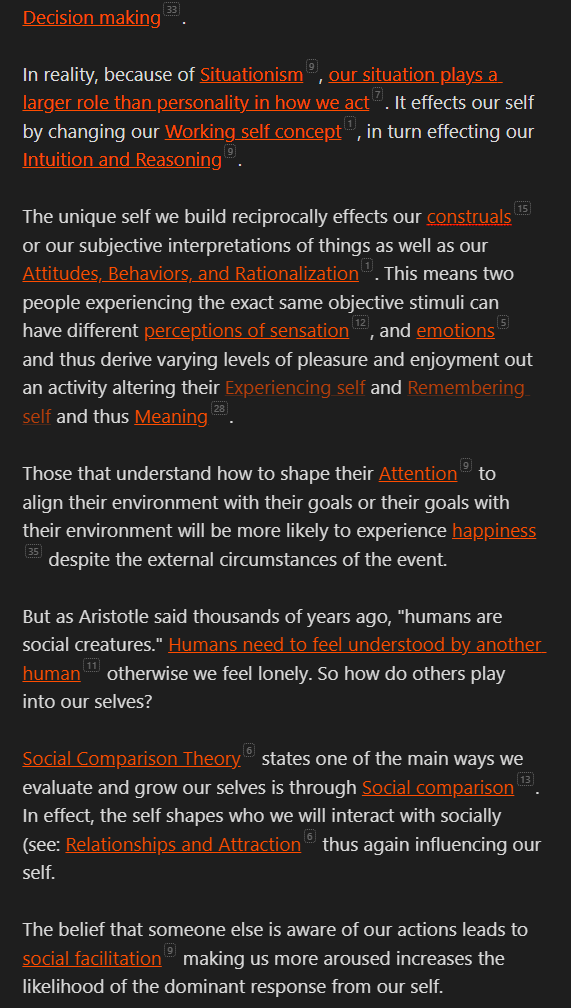

On any individual lecture day, I go into class and create a note out of the lecture we are doing that day.

Once I open up my lecture note, I add my standard new note template for a lecture:

The "#🟥" tag at the top alongside the "#lecture" is there so that the note pops up in [[My Lectures]], a MOC that shows all the lecture notes that need to be processed.

But I don't write down what they say verbatim.

Doing so would make me a cookie cutter student.

Instead, I wait 20 seconds to a minute before I even think about writing anything down. Despite my borderline love relationship with Personal Knowledge Management, I think on average students should be taking less notes than they think they should. By taking fewer notes than you think you need to we can use more mental bandwidth to understand the lecture while you have the professor there to ask questions.

While listening to lecture, I look for information that isn’t USE, Unimportant, Self Explanatory, or Easy enough to memorize on the spot.

Once I feel find something that isn't USE, I distill what the professor said in my own words and take inspiration from the popular Cornell Notetaking method by trying to frame my notes in the form of questions.

Let's see how I did in the Evolutionary Psychology note.

Evolutionary Psychologists believe that the fundamental thing motivating human action is the replication of genes into the next generations gene pool. During the lecture, three main arguments were brought up arguing against evolutionary psychology.

While taking notes I framed these three arguments under one big question as a header:

When I toggle this header it opens the three arguments which themselves are framed as questions.

Each of these arguments contains answers written in my own words.

Wording my notes like flashcards makes studying later on seamless. During a study session, I can open up my lecture notes and make my way through the questions by answering them in my head.

And by waiting 20 seconds to a minute before writing anything down, I strengthen the initial encoding of information by forcing myself to distill the professor's words.

If I ever need to add a slide to support my notes, I just take snip of an image from the slides and add it in. Here's an example:

🥜The Four Gs of Notemaking

Taking notes in this way is a massive step up but these notes are still isolated to the class we are taking notes on. To do the Conceptual part of conceptual notemaking you have to ask yourself the four Gs of notemaking. They are called this because all of them will help you grow your notes. But personally, I refer to them as the four questions of peanut butter godhood (I like peanut butter if you can't tell).

- "What does this remind me of?"

- "What is this similar to?"

- "How is this different from?"

- "This is interesting because?"

Once you have found an answer for one of these questions, write it down and link to or create another note in your system that provides an answer. I did this in one of the notes shown above about the naturalistic fallacy.

The naturalistic fallacy reminded me of a note I created earlier on the fact that not everything natural is good, a belief that conflicts with many of the "only organic" food eaters of today who make their claims off the admittingly terrible Western Diet (which I also link to).

The note on "not everything natural is good" links to a bunch of other notes like my Evolution MOC (see: MOCs), notes on Nazism, and notes on Nutritionism from Michael Pollan's book, In Defense of Food.

Here's a view of the back linked notes (notes that mention my "not everything natural is good" note) using the linked view.

And here's a view of the outgoing links for this note showing all the notes that link out from my "not everything natural is good note."

For more spatially oriented people (like me), seeing the connections in the local graph view can be helpful.

Now here's the cool thing.

Some of these notes linked in my "note everything natural is good note" have tons of links inside of them.

For example, my book note on In Defense of Food by Michael Pollan, links out to many other notes on nutrition science.

And all of these notes are second orderly linked to my original lecture notes on Evolutionary Psychology.

Isn't that cool!

My lecture notes have stopped being isolated to just my class but now relate to my own independent research in Nutrition Science that link out to tons of other notes.

You might be thinking, if you link notes from separate classes and your professor gives exams per chapter, how do you ensure you don't study notes from another class while studying for a specific class?

If this is something you worry about, I suggest tagging notes with the chapters you will need to study from. For example, if you have a note from Psychology 101 that you know the majority comes from chapter 3, tag it with #chapter3. Then when you are ready to study for your exams, you can create a dataview query that pulls only notes tagged with chapters 3 or whatever chapters you are studying.

This way you can still link to other related notes from classes you are taking to build a unique knowledge base, but only pull the notes you need to study for a specific class on a given study day.

To sum up the conceptual notemaking process goes like this:

- Wait 20-60 seconds before distilling notes in your own words as a question

- Reflect on the four questions of Peanut Butter Godhood

- Try to link to other notes or create a new note to link

Do this for an entire lecture, and you will have a beautiful personalized new block of knowledge.

Here's the local graph view of my whole Evolutionary Psychology note.

Repeat this for every one of your lectures, and something magical will happen.

You will begin to create a unique personal knowledgebase that scales across classes and semesters.

Look at the local graph for my entire Introduction to Social Psychology class. I put the depth of the graph to 2 (you can see notes that are second-order linked) so you can better see where everything is linking. The arrow points to my Evolutionary Psychology lecture note.

Here's the same local graph view but for my home page on my Behavioral Neuroscience class.

Oh and hey look! There's my Evolutionary Psychology Note.

After Class

What do you do with these notes after class is over?

As I said earlier, by framing the notes in the form of questions, they become perfect for studying off of like a flashcard or short answer question either alone or in groups.

Remember the "#🟥" tag we put on the notes earlier? I recommend going through your lecture notes that need to be processed when you have the time over the week and turning them into concept notes, notes that focus on one idea allowing them to be linked across your system and eventually combined to create things like essays, study guides, YouTube videos, and so so much more. After turning a lecture note into a concept note you can get rid of the "#🟥" and replace it with "#🟩" but if you get caught halfway done you can put a "#🟨".

As you go through your classes and learn more, you will naturally find holes and issues with the notes that you took earlier on. I like to make changes opportunistically, altering small things every now and then when they come up instead of going back through my notes in one heavy lift.

After the Semester

After the semester, I like to combine and organize all of the main concept notes I took from the class and organize them into a massive summarization MOC for the class as a whole.

Every time I do this process I come away with a much greater understanding for the concepts we learned throughout the class. But I do something even more important. I continue to link back to the class content in future semesters when relevant. In effect, my knowledgebase scales across classes and semester instead of remaining siloed.

Here's an example of my finalized MOC for my social psychology class.

Notetaking In STEM Versus Notetaking In The Humanities

The Zettelkasten system of notetaking with some adaptations can work for both humanities and STEM students.

It’s great for humanities because of how interdisciplinary it is making cross class and semester connections incredible. And it’s great for STEM because of how much previous concepts build off each other making cross semester connections invaluable.

I (Aidan) am a Psychology major (Humanities) and John was a Computer Science major so we know the differences between taking notes across disciplines. ### How To Change The Zettelkasten For If Your a STEM or Humanities Student

📜Humanities Students:

- Emphasis on interpretation and analysis: Humanities subjects often require critical analysis, interpretation of texts, and exploration of abstract concepts. Humanities students therefore might have longer interpretative style notes compared to the more number based nature of STEM students.

- Interdisciplinary connections: Humanities students frequently draw connections between various disciplines, such as literature, history, philosophy, and cultural studies. Their Zettelkasten may reflect more interdisciplinary connections compared to STEM students who might have more connections across time in the same discipline.

- Citations and references: Humanities students often engage with extensive academic literature, requiring meticulous citation management. This means they might have more notes on literature sources than STEM students. That’s right, if your in humanities your gonna get to build a whole library in your system!

The QAC Notetaking Method

Taking all these differences into account, I recommend humanities students consider taking some of their notes with the QEC method.

The QAC method stands for Question, Answer, Citation–we will be talking about it extensively later in the course when we get to lecture notetaking. Essentially when taking notes you create a question with an answer under it and a citation for where that answer came from. This not only forces you to write notes in your own words, but makes your notes valuable studying material for later on.

What better way to study than from questions worded in a way you understand?!

🧪STEM Students:

- Focus on scientific principles and formulas: STEM subjects rely on scientific principles, mathematical formulas, and empirical evidence. STEM students may capture key formulas, equations, and experimental methods in their Zettelkasten. They may also document scientific concepts, definitions, and empirical findings. Because STEM classes tend to build off of each other from semester to semester cross semester connections can be invaluable.

- Problem-solving and algorithms: STEM students frequently encounter problem-solving scenarios and algorithmic procedures. They may create Zettelkasten notes specifically dedicated to problem-solving techniques, step-by-step algorithms, or coding snippets. These notes can serve as valuable resources for future reference and application.

- Experimental design and data analysis: For STEM students involved in research or lab work, documenting experimental designs, methodologies, and data analysis techniques is important. They may include notes on statistical analyses, research protocols, or data visualization methods within their Zettelkasten.

- Visualization and diagrams: STEM subjects often benefit from visual representations such as diagrams, charts, and graphs. STEM students may incorporate visual elements within their Zettelkasten, creating visual aids to understand complex concepts or illustrate relationships between variables.

The PAS Notetaking Method

Taking the STEM notetaking differences into account, I recommend STEM notetakers use the PAS method rather than the QAS method to take notes.

The PAS method stands for problem, answer, citation. Essentially, you write down a problem, write down the annotations involved in solving it, and the solution. This method of notetaking once again gives you valuable studying material later on like with QAC for humanities.

My Secret Weapon In STEM Classes: Predict Answers To Questions Beforehand

Time and time again in my STEM classes I see students watching the professor while they solve a problem on the board.

This is a big mistake.

It’s a very passive form of learning.

My secret weapon in STEM classes is I try and solve the problem alongside the professor before they do. After an explanation of something, Professors in STEM classes will often go through example problems on the board. It’s useless to write down what the professor writes and save these examples in your notes because simply looking at an example problem that’s already completed does nothing in developing understanding. In fact, it will probably just make you think you know what you’re doing more because of humans’ tendencies for overconfidence.

Instead, you should try and do the problem yourself in your head or on a spare piece of paper.

Then you can check your process alongside the professor.

For example, in my Statistics class we were learning about Analysis of Variance, a statistical technique which is used to assess statistical significance inside of studies that have more than two levels of a factor.

During the class this example question came on the board:

Most students, when seeing this would follow the professor as the question is answered.

Instead, I started going through each of the questions myself on a piece of paper. Whenever I was confused by a section, I could refer to what the professor was doing for help. This also gave me a better idea of what to take notes on and what to not. If I stumbled on a section of question it’s probably something I should take notes on.

Plus it means you have to study less as the act of doing the problem yourself is a active process.

Conclusion: The Art of Compounding Knowledge

Using my Conceptual Notemaking process, I'm building a unique interconnected body of knowledge, a culmination of my personal ideas and interpretations of my classes, own thoughts, conversations, and information consumption outside of school.

Instead of going from semester to semester with a clean slate having forgotten everything from the previous year, I build a unique personal knowledgebase that scales across semesters.

My knowledge compounds growing more and more useful the more notes I have rather than less.

I wake up every day with wonder and curiosity about what new notes and connections I will make.

I have reignited my joy for learning.

While I can't guarantee that this notemaking process will work for you, I strongly encourage you to try it out for a few weeks at least.

If you resonated with this post you should check out my free email course: 3 Days to Lecture Notetaking Mastery In Obsidian.

By the end of this free email course, you will:

- Have a systemized process for notetaking and studying from your lectures

- Understand how to build a knowledgebase that scales across classes and semesters

- Be amazed that you did it all in 3 days