🧠AIP 83 This Forgotten Psychology Theory Could Change The Way We Learn EVERYTHING

Yes, you read that right. I’m using video games to learn--specifically to reach intermediate-level Spanish rather than the beginner-level I had after four years of traditional education.

I realized video games power for learning languages after exploring into a revolutionary yet obscure theory known as ecological psychology. The challenges it brings to the traditional methods of psychology could revolutionize teaching and self-directed learning as we know it.

But that’s not all—I’ve found ecological psychology functions as a philosophy as well as a psychological theory. Exploring it has helped me not only understand and live more in harmony with myself, but with others and the world as well. I hope it can do the same for you.

Buckle your seat belts because this will be a wild ride, and I don’t follow the speed limit.

The Psychological Theory Everyone Forgot About: Ecological Psychology

It was the mid-20th century, and psychologist James Gibson was beginning to realize that something was seriously wrong with the way most psychologists thought about the fundamental question every psychological theory attempts to solve: how do we as organisms perceive, make decisions, and act in our environments?

The problem was most theories at the time emphasized the organism or the environment too much.

The dominant psychological theory at the time was behaviorism, which was founded on the idea that all behavior is simply a matter of external reinforcements—which promote behavior—and punishments—which diminish behavior. Most behaviorists didn’t believe our internal landscape was very deep. Solely through external rewards and punishments, we could create any desired behavior.

B.F. Skinner—one of the leading behaviorists—famously said, “give me a child and I’ll shape him into anything.” Humans were seen as hedonistic calculators but with more existential dread and fewer batteries.

In response to the behaviorists' overemphasis on the environment, the cognitive revolution was sparked including a range of theories that put the most emphasis on the organism.

The cognitive revolution included theories such as cognitive psychology which analogized the mind to a computer putting emphasis on the brain (our CPU), memory (Hard drive), and information processing (RAM) as the root of how we perceive, make decisions, and act. It also included theories like psychoanalysis (which was around before the cognitive revolution but gained traction when it occurred) that emphasized the unconscious mind’s influence on organisms. And finally, there were the humanists who emphasized individual potential and stressed the importance of growth and self-actualization.

Naturally, all of these psychological theories clashed against each other “especially with behaviorism” creating quite a rave in the psychological community.

It was in this warzone Gibson began developing his theory of ecological psychology. Ecological psychology comes from the study of ecology, which explores the relationship between an organism and its environment, and psychology, which explores the human mind and how it interacts with itself, others, and the world.

Ecological psychology emphasizes neither the organism nor the environment; instead, it emphasizes the organism-environment relationship.

Gibson felt traditional psychological approaches were putting too much emphasis on the organism in isolation. Humans, we do like to love ourselves. He argued you can’t answer the above question outside the context of the environment.

Unfortunately, he wasn’t taken seriously. Ecological psychology was ahead of its time. For the other psychologists to accept Gibson would mean putting all their theories fundamentally into question. Gibson was like a chef trying to explain soufflé to a group of hunter-gatherers that hadn’t invented fire yet.

But that wasn’t the only reason. Ecological psychology was hard to research and had tons of difficult implications. Because of its emphasis on the organism-environment relationship, lab studies—the traditional method of psychological study back then—were hard to do. The implications (which we will get to further in this article) were vast. It could mean personalizing all learning to the individual, accepting the uncertainty of a non-linear approach to perception, decision-making, and action, and de-emphasizing the organism's importance in isolation from the environment.

For these reasons and more, ecological psychology has gotten relatively little attention in the public's eyes to this day. It wasn’t mentioned whatsoever in any of my psychology classes at Cornell. The only reason I discovered it was talking to Danny Hatcher on my podcast.

Let’s change that.

We’re going to explore exactly what ecological psychology is, why it has helped me learn Spanish through video games, and how it could change the way we learn everything.

The Problems With Traditional Approaches And How Ecological Psychology Addresses Them

To understand ecological psychology, we need to return to the fundamental question all theories of psychology are trying to answer: how do we perceive, make decisions, and act?

For the rest of this article, I will refer to the main psychological theories that have tried to answer this question as the “traditional approaches” (e.g., behaviorist psychology, cognitive psychology, etc.). It’s just that most of them are similar in the fundamental assumptions they make about answering the question above.

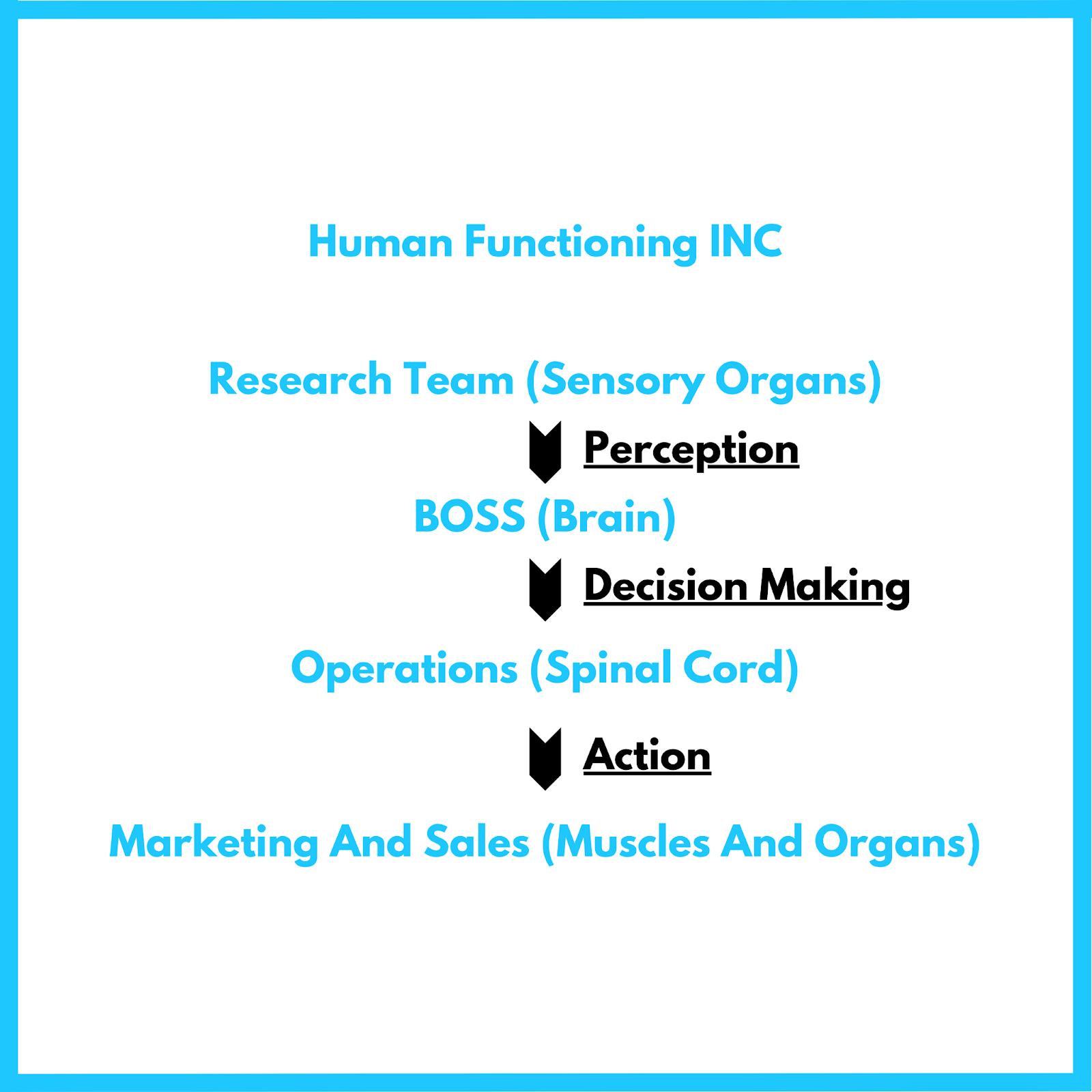

To understand the traditional approach to answering this problem, I like to use an analogy Gray R (2021) used in his book How We Learn to Move that of our brain like the CEO of a company “HumanFunctioningINC”and the disparate parts of our body as divisions and individual workers inside the company[^1]. The sensory parts of our brain take in stimuli from our environment and interpret them through processing memories and connecting to our schemas. This gets sent to the planning and decision-making parts of our brain which gives orders down the chain of command “the spinal cord” to the various organs and muscles of the body which finally spark action.

There are three key problems with this view of perception, decision-making, and action.

Problem 1: It isolates the organism from its environment.

The reality is we don’t perceive, make decisions, and act in white voids. We do so in the context of environments. The environment fundamentally alters how we percieve, make decisions, and act as anyone who has been on a diet and walked into a room with a box full of donuts can attest (definitely not me, cough cough).

Skills grow in the context of the environment you grow them in. Like a tree planted on foreign soil, we can’t simply take train skills out of context and plug them back in. Neither can we transfer skills across environments like playing chess to better our “strategic thinking.”

Emphasizing the organism too much has another insidious implication. Those who don't function "normally" in society are indirectly being told their parts are faulty. They aren't working correctly. And they must be fixed.

Problem 2: It treats perception, decision-making, and action as if they are a highly linear relationship when, in fact, they are very non-linear.

Thinking psychology is linear is like thinking the fastest way through a grocery store is a straight line; have fun crashing into the cereal aisle. Yet, linearity is comforting because we can understand it. Humans love to attribute cause-and-effect relationships to things.

The reality is, our psychology is like a dumpster dive—there's a bit of everything in there. You've got something from your morning cereal, a sprinkle of your mom's questionable 80s habits, and a dash of the emergency room ambiance where you were born.

Problem 3: It seems as if there is one optimal solution solving certain problems.

If perception, decision-making, and action happen linearly, it should be easy to plug and play a certain “optimal” solution across contexts to work with most individuals.

When we look at many traditional school and workplace settings, this is exactly what happens. Often, people are given the same problems with one “right” solution, neglecting the need to adapt to their specific organism-environment relationship. You can also see it in modern productivity and self-improvement culture where cliche generalized advice is often given out, thinking it will work for everyone.

How Does Ecological Psychology Address These Issues?

Let’s look at how it addresses each of the three problems mentioned above.

Solution 1: Look To The Organism-Environment Relationship Rather Than Just The Organism

Gibson's main point in his theory of ecological psychology is that organisms don’t exist in vacuums of space; we are both embodied—our mind exists in a body—and embedded—we exist in environments (Gibson J. J., 1979)[^2].

The differing relationship between each organism and its environment changes its perception, decision-making, and action.

He turned this idea into his revolutionary concept of affordances. Affordances are opportunities for behavior given by the relationship between an organism and its environment.

Perceiving affordances is to carve the world up in meaningful units of action rather than using the meaningless units of physics. In Gibson’s words: “The perceiving of an affordance is not a process of perceiving a value-free physical object to which meaning is somehow added in a way that no one has been able to agree upon; it is a process of perceiving a value-rich ecological object. Any substance, any surface, and any layout has some affordance for benefit or injury to someone. Physics may be value-free, but ecology is not”[^2].

For example, some trees afford climbing because of how they grew, but only for some people. Individuals with certain constraints—perhaps those who are particularly good climbers or have tree climbing equipment—afford climbing the tree, whereas for others, it doesn't.

Some trees, however, are so high, they afford climbing for nobody. Someone gave this tree too much water.

Another example: a high step might afford stepping for me because I’m Dutch and taller than you, muhuahahah, but it might be a wall for someone else, as was shown in one study on staircase height and affordances (Warren W., 1984)[^3].

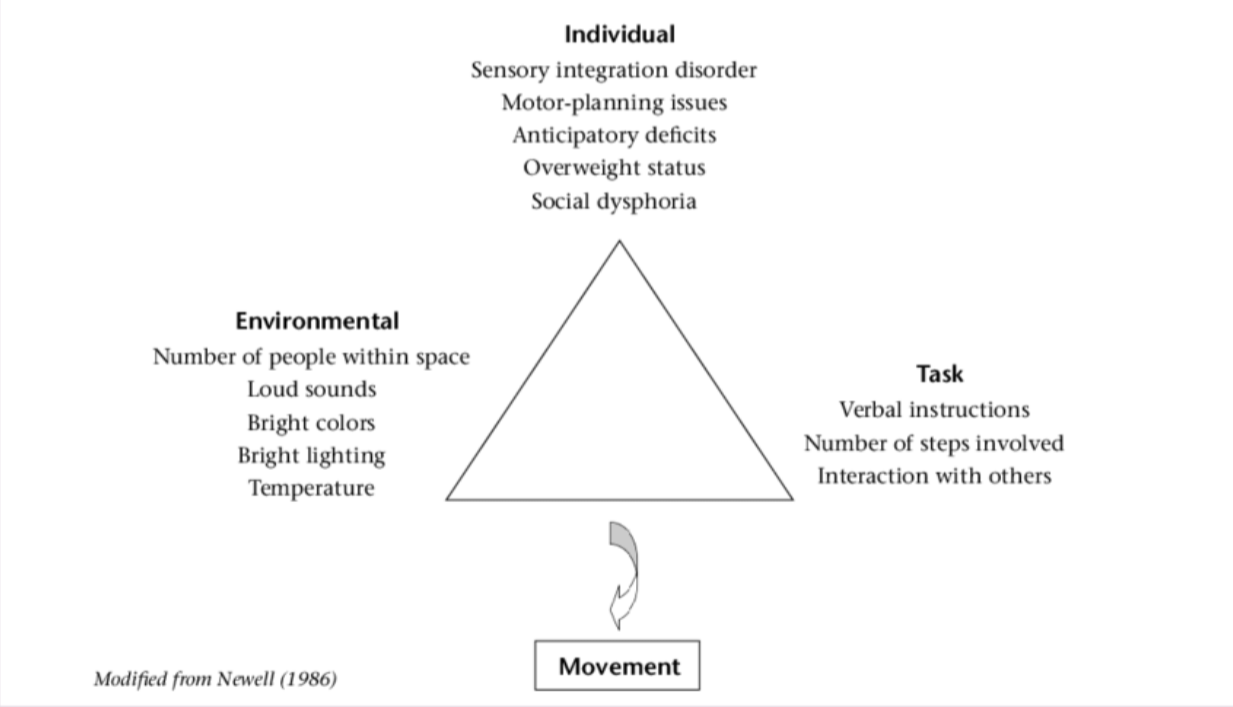

You may have noticed I used the word constraints up above. This is another huge concept inside ecological society proposed by Newell K. (1986)[^4]. Constraints are elements of the environment, the task, or the individual which create limitations on affordances. Newell originally talked about them in the context of movement, but they can also be applied to psychology.

Environmental constraints might include temperature, the material of the field, or weather if Zeus is angry. Task constraints might include rules of the activity, whether explicit or implicit, the size of a ball in a sports context, or the number of players. Individual constraints might include fatigue, height, or muscle mass.

Differing constraints can change an organism's affordances. For example, one of my best friends has the constraint of having severe ADHD. The only way she can afford herself to do homework, is by doing it with someone else while listening to music to keep herself from getting bored and stopping. She sets reminders for everything because otherwise, she’ll forget. She’s constantly doodling during class. Some people look at her and think what she’s doing is silly (and it probably would be for them) but neglect the differing constraints between them.

Stop. Think for a moment how cool that is.

Every person, every insect, every organism has a different organism environment relationship. They have different constraints and affordances and therefore perceive, make decisions, and act in the world differently.

Isn’t that insane?!

Sometimes while petting my cats I wonder what is going on in that head of theirs—oh I mean that organism environment relationship—much catchier if I do say so myself. What a simple life they live. Drinking milk, eating food, and sitting around.

Solution 2: Realize The Non-Linear, Dynamical, Interdependent Relationship Between Perception, Decision-Making, And Action

In the business analogy from beforehand, Human Functioning INC makes perception, decision-making, and action out to be clear linear processes.

In How We Learn To Move, Gray R. (2021) proposes an alternative analogy for viewing perception, decision-making, and action—the no-boss view of self-organization—or what he calls “Self-Organization LLC”[^1]. Self-organizing systems exist everywhere and work without a boss. To understand how self-organization works, let's look at one common example you see everywhere: a flock of birds.

As Gray explains, “the business model used by a flock of birds is one of self-organization. That is, the order and structure in the company arise from the interactions between the lower-level components of the system, not from some rules or a plan given by a higher-level, central controller. The workers are organizing themselves using only the information available to them, without needing a boss” (p. 38-39).

No one king bird—King Deedeedee you might say—controls all the other birds movements. Rather, all the birds perceive and react to their fellow birds in response to movements, wind, and other things. In ecological psychology, this is called perception action coupling where perception and action aren't separate linear processes but one interdependent dynamical system.

What the birds perceive influences how they act and how they act changes what they perceive.

If that’s not beauty, I don’t know what is. Self-organization is seen throughout nature from structure formation in cells, to patterns formed in inanimate objects like sand, to the schooling of fish. What happens if we fire everyone from Human Functioning INC and replace them with Self-Organization LLC? Suddenly, the perception, decision making, and acting teams are no longer part of a linear process but rather a continuous interdependent dynamical system.

Needless to say this makes life a lot more complex, but rightfully so.

As boss, we understand we can’t separate parts of our organization and fit them back together like jigsaw puzzles. We must respect the whole as different from the sums of its parts. We must foster relationships between individuals and cross team interaction. We must accept we don’t know everything and get input for decisions from the bottom of the ladder instead of just us.

The implication of this notion feeds into our final solution.

Solution 3: Realize There Is No One “Correct” Way To Do Something

If perception, decision-making, and action happen linearly, it should be easy to plug and play a certain ”optimal” solution across contexts to work with most individuals.

The thinking behind this breaks apart as soon as you recognize the differing affordances and constraints between individuals.

Let’s jump into the world of tennis for an example. To successfully hit a tennis ball in the same way over the tennis court, you need to perform the same movement, under the same conditions.

Here’s the problem: the constraints are always changing!

Each tennis ball hit differs in spin, speed, direction, and more. Going back to Newell’s model of constraints, the individual constraints might differ—an athlete could be more fatigued, taller, or have different-length arms compared to another athlete. The task constraints might differ—maybe you're playing doubles instead of singles or volleying instead of serving. Finally, the environmental constraints could differ—it could be raining, windy, or worse, hailing (yup it’s happened to me).

If we use the same movement pattern among varying constraints, we won’t get the same outcome.

Therefore, as Gray R. (2021) explains, if we want to produce the same outcome, under ever-changing conditions, we have to use a different movement every time. This is a critical insight coined by Bernstein N.A. (1996), which he called “repetition without repetition”: we repeat action outcomes (i.e. hitting the ball over the net) by changing our movement patterns to adapt to the varying constraints of our environment[^5]. Hence, repetition without repetition.

Therefore, the key to becoming skilled is not learning one “gold standard” technique but learning to produce the same outcome by adapting movements to differing constraints.

If you analyze the top athletes in sports today, you’ll find a huge diversity in movement patterns. As Gray R. (2021) further explains in his book, skillful movers in the same discipline not only differ in movement patterns from each other—inter-movement variability—but also have significantly different movements themselves during play—intra-movement variability.

This doesn’t just apply to sports but to everything.

Different productivity methods work for different people. Different routines work for different people. Different learning principles work for different people.

The trick is to expose people to different environments different organism-environment relationships and help them self-organize their own best solution.

How Ecological Psychology Can Help Us Supercharge Our Learning

Why Am I Using Video Games To Learn Spanish?

Let's start by understanding the problems with my Spanish learning in high school. I won't lie; my teacher tried. She gave us lessons on grammar, vocabulary, and punctuation with gusto. But the biggest problem is that she didn't take into account the environment we would be using our Spanish in or the individual constraints of each learner.

There were A LOT of learning vocabulary words we forgot just weeks later because we never used them in our real lives. We learned about words for traveling, city life, being in a hospital, and more. Here’s the thing: our school is in a town so rural, the GPS just gives up and says, “You’re on your own, buddy.” There are more cows in my town than girls. So when am I going to talk about words for traveling, cities, or hospitals in Spanish? It didn’t make sense for the organism-environment relationship.

There was also no attempt to learn words related to the individual interests of each learner or recognition of the environment in which we would use those words. Our learning was decontextualized. In real life, we would use Spanish by having freeform conversations and yet we rarely had any during the class. The only people we spoke Spanish to were our classmates, so we almost never heard what native Spanish speakers sounded like.

We learned Spanish, sure, but we learned Spanish for the classroom. I guarantee you that if we had to have an actual conversation with a native Spanish speaker, we would have been screwed.

So, how is my video gaming any better?

Firstly, I actually enjoy playing video games. So it makes me more intrinsically motivated to learn, and hence why I am learning outside of class. I’m motivated to learn Spanish well because if I don’t I won’t be able to understand what is going on in the video game at all.

Secondly, learning from video games gives me a personalized environment to directly apply my Spanish to. This environment is allowing me to learn words specific to my interests and in context.

Thirdly, I'm hearing native Spanish speakers speak. This affords me the opportunity to speak in Spanish with natives myself if I ever go to a Spanish-speaking country in Latin America.

Now that we have discussed some of the reasons ecological psychology has led me to use video games to learn Spanish, what are some other general learning principles we can draw from the theory?

Don’t Separate Skill From The Environment It’s Embedded In

Transfer has long been thought of as the holy grail of education. The idea is what we learn in the classroom context will transfer outside of the classroom. Learning English will deepen our emotional resonance, math will deepen our logical skills, etc.

But Haskell (2001) states “Although some disagree, most researchers and educational practitioners ... agree ... that meaningful transfer of learning is among the most—if not the most fundamental—issue in all of education. They also agree that transfer of learning seldom occurs” (Haskell, 2001, pp. 3-4)[^6].

Why is the transfer of learning so bad in education?

Murrin (2016) states, “rather than demonstrating how a truth was discovered through inductive reasoning (that is, the steps in which understanding was established, which can be more important than the truth/fact itself) the truth/fact is simply fed to passive students who have no idea what to do with it and, typically, are not taught how to apply/use it, which is why transfer does not occur. If one does not know how to apply/use it in a real-world scenario, what purpose does it serve? It is like an empty vessel. It is simply an object/idea with no significance, but perhaps awaiting rediscovery, like an uncovered archeological object that stumps scientists’ understanding of its use” (Murrin B., 2016, p. 15)[^7].

The ecological psychologists have a solution for this: don't separate skill from the environment it's embedded in.

Transfer of learning is so bad because it's woefully indirect. For any learning endeavor, whether in school, self-directed learning, or the workplace, ask yourself, how can I adapt this to be as direct to the environment I want to use it in as possible?

Skills don’t just exist in an organism. It exists in the organism-environment relationship.

Scott Young (2019) gives four ways we can make learning more direct in his book Ultralearning[^8].

Firstly, we can create a learning project. This gives us an avenue to apply our learnings. For example, I created a learning project for my 30 days to learning pixel art , my spanish language learning , and my journey to learning periodization in the gym .

Secondly, we can create a simulation of whatever we are trying to learn. For example, pilots use flight simulators to get pilots ready before using a real plane.

Thirdly, we can immerse ourselves in the actual environment we want to use the learning. For example, an intense language learning project could involve moving to a country which predominantly speaks that language and immersing ourselves in the culture.

Finally, we can create analogies. Analogies connect whatever your learning to the real world. I’ve used them countless times throughout this article to explain concepts like constraints, affordances, and self-organization to you.

Of course, direct learning isn't always possible. I'm happy that in history class, we never reenacted an actual battle with real guns. Sometimes, learning should be done for learning's sake, with no need to transfer. Some things need to be simplified because of a lack of resources. But there's no question we can fight the transfer problem better than we are with an understanding of ecological psychology.

Give Personalized Problems And Questions, Not Blatant Solutions.

If everyone has different constraints and affordances, then it doesn't make sense to give everyone the same solution to problems.

That's like asking someone to set sail from different starting points but giving them the same directions, supplies, and no map. Instead, an ecological approach would involve giving more problems and questions.

Problems and questions encourage learners to explore and self-organize their own solutions, which are likely to fit more in line with their unique organism-environment relationship. This promotes critical thinking and problem solving.

Now in future situations, those people can better solve their own problems rather than looking to someone for the “one best solution.”

For example, math is a notoriously hated subject for many in school. I think one reason is that everyone gets the same abstract, boring math problems with only one answer.

But what if we asked the math-hating jock to try and calculate what football team he thinks is going to win the playoffs using algebra, arithmetic, and probability. Suddenly, they have an interesting, personalized problem to solve.

Similarly, we could encourage athletes to explore and find their own movement solutions that fit with their body's individual constraints. That's how Fosburry revolutionized high jumping when he invented a completely new style of jumping backward that has since been coined the "Fosbury Flop."

While I’m encouraging exploration, it is worth mentioning as a caveat that imitation can be great for learning, especially in the beginning of a learning endeavor. You can't innovate until you imitate. As Young S. (2024) explains in chapter eight of his book Get Better At Anything, many of the greatest scientists, artists, etc., in history started out as apprentices[^9].

However, the problems come when the imitation never stops. Or when personalization isn't even attempted in the first place. With an application of ecological psychology, we can ensure this doesn’t happen.

A Changing Time For Psychology... Or Life In General

Unfortunately, Gibson, Bernstein, and Newell--the three great contributors of ecological psychology--aren't alive anymore.

But if they were, they would be ecstatic knowing ecological psychology is finally starting to make its leeway into the modern psychology field.

And it continues with you.

Simply applying the insights of ecological psychology into your own life--organism-environment relationship, constraints, affordances, repetition without repetition, self-organization, and more can help it spread. Try and talk about it with someone. Use one of the analogies I mentioned above. See if the theory resonates with you.

Ecological psychology is completely changing how I see learning, but I think it's more than that. I see it not only as a psychological theory but as a way of life, a philosophy. One in which we respect the individual's relationship with the environment. We don't assume other people should feel, think, or behave the same way as us. We see the beauty in the non-linear, dynamical, interdependent relationship of perception, decision-making, and action.

Instead of putting ourselves on the pedestal, we humble ourselves by recognizing our environments. Instead of seeing our beliefs, skills, etc. as the best way we realize it might be the best way for us.

So go think outside the box—or in the box—because otherwise, you would be neglecting the organism-environment relationship.

News From The Channel!

Latest On De Podcast - E43 Scott Young: How To Get Better At Anything : How can you master hard skills more quickly? Accelerate your career? Be more productive and live a better life? Since 2006, Scott Young has been writing to try to find answers to these questions with books such as Ultralearning, hundreds of articles, and courses such as Make It Happen. In the last few days he has finished another major book on learning called Get Better At Anything.

In this podcast you will learn:

- Why success is often a better teacher than failure

- Why copying and innovation are complementary

- Why most learning doesn't transfer between contexts

My Best Insights:

P.S. Some of the links below are Amazon affiliate links.

Book - The Eye Of The World: a 15 book epic fantasy series I’m exploring with my brother. We have already ventured into the absolutely massive Stormlight Archives and are using this as our next rodeo. I’m excited, immersing yourself in a big series and losing touch with your own self at times is so cool.

References

[^1]: Gray R., 2021. How We Learn to Move: A Revolution in the Way We Coach & Practice Sports Skills. https://amzn.to/4bECqkq

[^2]: Gibson, J. J. (1979). The Ecological Approach to Visual Perception. Psychology Press. https://amzn.to/4bzmYpY

[^3]: Warren, William. (1984). Perceiving Affordances: Visual Guidance of Stair Climbing. Journal of experimental psychology. Human perception and performance. 10. 683-703. 10.1037/0096-1523.10.5.683.

[^4]: Newell, K. M. (1986). Constraints on the Development of Coordination. In M. G. Wade, & H. T. A. Whiting (Eds.), Motor Development in Children: Aspects of Coordination and Control (pp. 341-360). The Netherlands: Martinus Nijhoff, Dordrecht. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/978-94-009-4460-2_19

[^5]: Bernstein N. A., (1996). On Dexterity and its Development. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Publishers. http://graphics.cs.cmu.edu/nsp/course/15-869/2012/papers/BernsteinOnVariation.pdf

[^6]: Haskell, R. E. (2001). Transfer of learning: Cognition, instruction, and reasoning. Academic Press. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-012330595-4/50003-2

[^7]: Murrin, B. (2016). The Transfer of Learning: The Meaning of Learning Itself. Applied Education Foundation. https://appliededucationfoundation.org/images/essays/The%20Transfer%20of%20Learning.pdf

[^8]: Young, S. H., (2019). Ultralearning: Master hard skills, outsmart the competition, and accelerate your career (First edition.). Harper Business, an imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers. https://amzn.to/3KrSQkZ

[^9]: Young, S. H., (2024) Get Better At Anything: 12 Maxims For Mastery. Haper Business. https://amzn.to/3QMrwRV

Got questions? Hit "reply"! I read every email (yeah people are surprised!) 🤗 Thanks for reading!

Cheers, 🥜

Aidan

Aidan Helfant 👋Say hi on Twitter , My Podcast , or YouTube

Thank you for being part of the journey!🎊 Whenever you're ready there are three ways I can help you:

The Art Of Linked Reading: This course helps people who struggle to understand, connect, remember, apply, and smartly share insights from non-fiction books learn to do so with linked notetaking apps like Obsidian, Tana, Logseq, and more.

Obsidian University : a pre-made Obsidian vault, templates, and video course helping you level up your notetaking and studying, fall in love with learning, and get good grades in less time so you have time for other parts of college.

⭐You can also share this newsletter here.

If you would like to update your email settings, choose from the options below:

- Unsubscribe from just Aidan's Infinite Play.

- Unsubscribe from all future mailings. This will make me sad. But hey... I get it. You're busy. Just know that once you click this link you won't receive any more emails from me.

- Update your profile here.